When I was first introduced to the concept of artist books I remember being struck with the physicality of it, the way a beautifully written work, or a unique set of illustration could be bound in what is a work of art in and of itself. So often when the debate arises between a physical book and a digital edition, the points discussed relate to the ways in which people read, maybe expanding to touch on the smell of the book that one lacks in an e-version of the same text. Seldom do I hear the argument for an e-book approach reading as anything other than the consumption of a text, and the delve into the realm of artist-books sent me thinking about books as objects, or rather books as “body” in a way I hadn’t quite dwelt on prior.

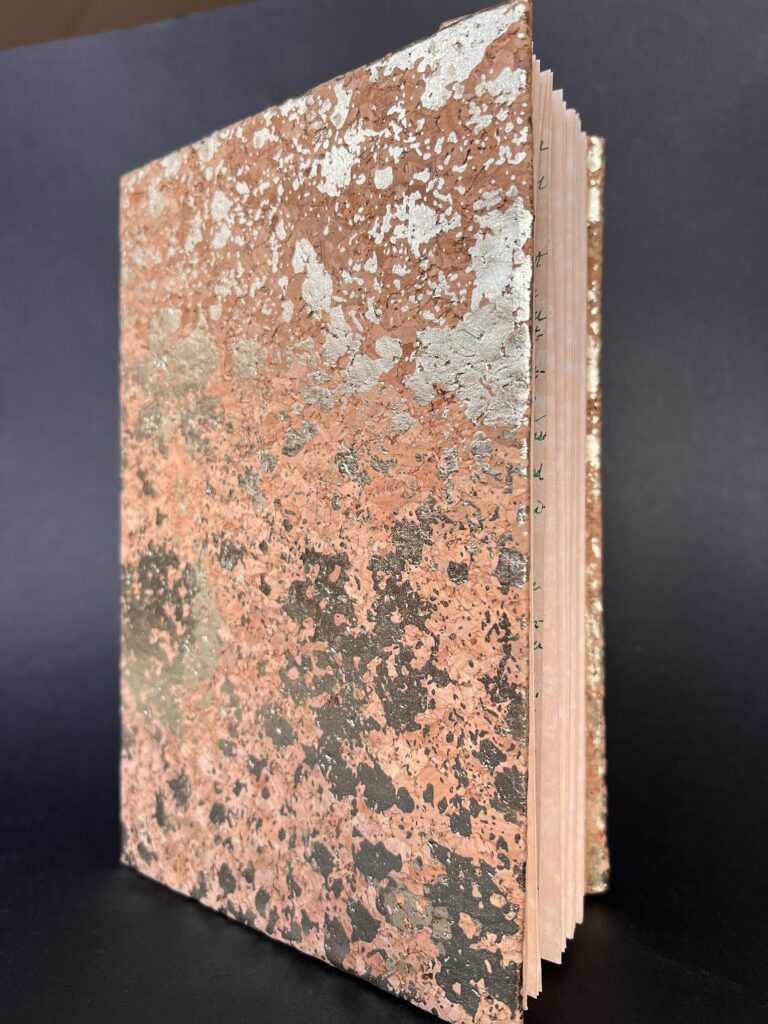

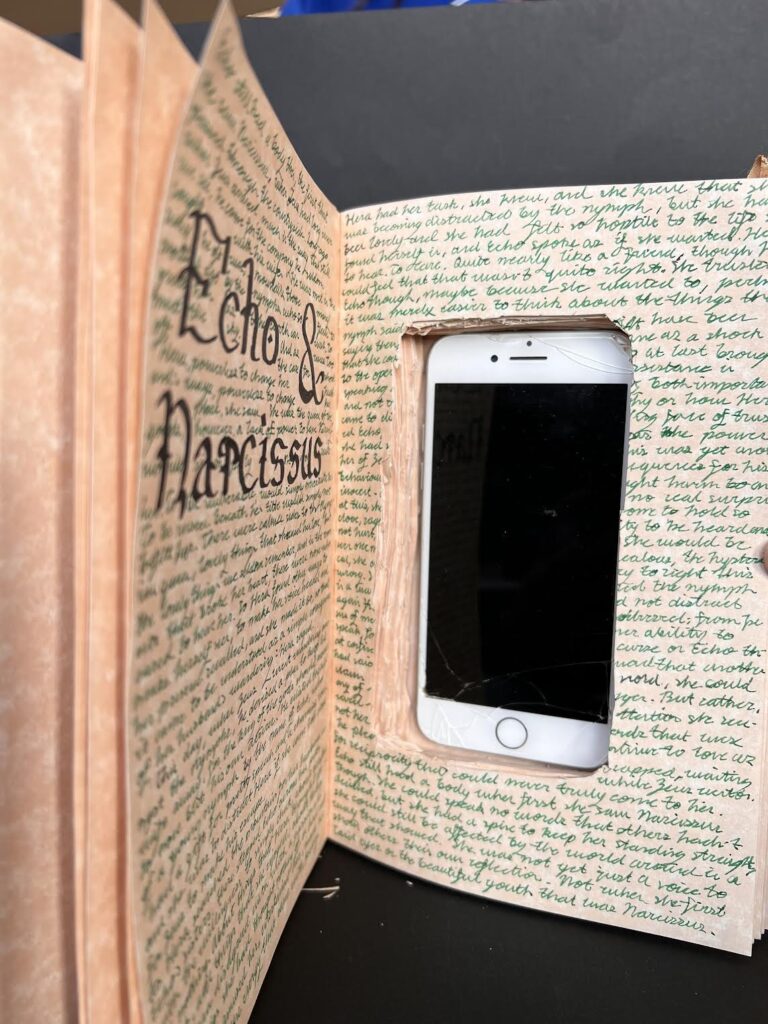

A book, with proper care, can last thousands of years, everything it had ever come into contact with making its impression on the object in some way, much as people are shaped and show the signs of their experiences in the world. In a similar way, a well-loved book and the person who loves it often make their marks upon each other: spines get bent, from hunching over for comfort and better light, and from opening to a favorite page enough to make a crease, light may wash the printed page, and eyes get strained from making the best of the fading day, and so on. My point is that there are bodies involved, in books and in the living, in a way that the “Cloud” disrupts. In my project, I constructed my book myself, doing everything from folding and sewing the signatures, to binding it in board and fabric, writing in it by hand. I aimed to create a thing of beauty that belongs to the physical, and human, world. The disruption comes in the form of the broken phone. While a book can outlive us by millenia, these things that are meant to represent our technological advancement become irrelevant in a matter of several years, their bodies discarded in favor of a newer model, yet their memories transferred in a fashion that makes the change of bodies as irrelevant as their death.

This is where my title comes from. I made use of “Echo”–both the myth and phenomena–to call attention to this lack of physicality. An echo is merely a disembodied thing, your voice, and yet not you, as it is not quite you who is making the continued sound. It is a reflection then, in a sense, much as the ever-advancing algorithms used for things like social media and targeted ads are made to know you better than you know yourself in order to show you only what you want to see. In the physical world, there are no algorithms; if you walk into a bookstore for entertainment rather than look to your phone, things are slower and the options are border because they haven’t been chosen specifically for you. The phone quite literally cut into my book is meant to show the alteration of expectation thus bound in each form of media (book versus device), and indeed, the existence of writing on only a few pages of the entire book is meant to the level of distraction presented by even the idea of a smartphone from modes of less technologically current forms of education and entertainment.

To view the digital content of “Echo,” click on this hyperlink.